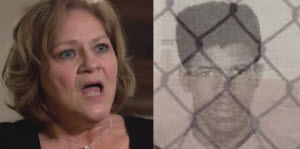

The morning of 17 April 1972 will be forever etched on Leontine Rogers’ memory.

The 17-year-old trainee beautician, known as Teenie, woke up early, had breakfast and drove her 23-year-old husband Brent Miller to work. He was a guard at the notorious Angola prison in the state of Louisiana.

A few hours later, she was sitting in class at the beauty school, when her sister turned up out of the blue.

“There’s been an accident. Brent is dead,” she said.

Teenie’s world collapsed. The couple had been married for just three months. Brent had been found dead in a cell with multiple stab wounds.

“Brent was my whole life. He was witty, handsome and talented. He sang and played the drums. He was an all-round good soul. I couldn’t imagine going on without him. It was so hard,” she told Amnesty International.

But what neither Teenie nor Brent’s family knew was that from that point on, their lives would become embroiled in a legal case that has spanned nearly half a century.

The trials of Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace were deeply flawed. Their convictions reflected the rife discrimination and corruption in Louisiana’s justice system.

A third man, Robert King, was accused of planning the murder from another jail.

All three were placed in solitary confinement following the murder. Together they are known as the “Angola 3”.

In a bizarre turn of events Teenie found herself fighting for justice – not just for her husband – but also for the men convicted of his murder.

Pointing the finger of blame

Brent and Teenie met in the early 70s in a tight-knit community next to the Angola Prison, where most of the prison staff and their families lived. Her father was also a guard.

The prison, built on what used to be a slave plantation called Angola, was known for its brutal treatment of detainees.

Racism was rife behind the tall concrete prison walls. Inmates were racially segregated and guarded exclusively by white officers. Murder and rape were endemic.

Amongst the hundreds held in Angola were Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace, two African American men who had been convicted on unrelated cases of armed robbery.

In a bid to improve prison conditions, they founded a chapter of the Black Panther Party – a popular revolutionary movement at the time.

But their activism didn’t sit well in the prison.

Almost immediately after the discovery of Brent’s body, covered with stab wounds, Herman and Albert were placed in small airless isolation cells.

The small correctional community of Angola was in turmoil. Many wanted answers and fast.

“We all grew up there and to have one of us taken out like that. Everything changed in Angola after that. No one trusted one another,” Teenie explained.

It was too much for Teenie and her family – they left to watch the trial from afar.

“Show” trial

While Albert and Herman claimed they were innocent, their trial was shockingly flawed.

Prosecutors failed to produce any physical evidence linking the men to Brent’s murder. A bloody print found at the murder scene was used as evidence, even though it did not match those of the men accused of the murder.

Since the original trial, evidence has emerged that the main eyewitness was bribed by prison officials to give statements against the men; and that the state withheld evidence about the perjured testimony of another inmate. Other witnesses retracted their testimony.

Robert King was finally released in 2001, after 29 years in jail.

Meanwhile, Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace continued to languish in solitary confinement.

Lawyers, private investigators and human rights advocates have continued a tireless campaign for their release.

A fateful knock at the door

In 2006, Billie Mizell, an investigator working for the campaign to free the men, knocked on Teenie’s door. It was only then she realized that there might have been a terrible miscarriage of justice.

“Billie said she wanted to talk to me about Angola. I was fascinated someone would want to talk to me about what happened. She started showing me evidence … the bloody fingerprint, the fact was that they did not belong to any of the three they had in prison so it just got me thinking … and after seeing all the evidence, I believe them to be innocent,” said Teenie.

From that moment and despite opposition from members of her community back in Angola, Teenie joined the campaign against the convictions.

Justice must be done

Progress has been painfully slow.

Last year, after nearly 40 years in solitary confinement, Herman Wallace was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

When Teenie found out she applied to visit him in prison, but all requests were denied.

“The moment I found out that Herman was dying it just broke my heart. I wanted to see him, I wanted to talk to him. I wanted … forgiveness. I wanted to let him know that I believed he was innocent, and I wasn’t able to do that,” said Teenie.

Finally a US federal court ruled that his trial had been unfair. Sadly it came too late for lasting benefit. Herman passed away on 4 October 2013, just three days after being released.

Albert Woodfox – last chance for freedom

Albert Woodfox is the last remaining member of the “Angola 3” still in prison. He has now spent over half of his life in isolation for a crime, Teenie believes, he did not commit.

Despite having his conviction overturned three times, he waits behind bars while the State continues to appeal.

The 67-year-old is confined to a 2×3 metre cell, 23 hours a day. He is only allowed out to exercise alone in a small outdoor cage or to walk along the cell unit corridor and shower.

Albert’s lawyer has said he now suffers from claustrophobia, hypertension, heart disease, chronic renal insufficiency, diabetes, anxiety and insomnia – the shouting and screaming from adjacent cells makes sleeping very difficult.

After nearly four decades in isolation, he is still waiting to see if the Appeal Court will uphold the decision of a Federal Judge, a year ago, to overturn his conviction.

If it finds against him, he is most likely to die in prison.

In the meantime, Teenie will continue to fight for justice, not just for Albert Woodfox, but for the memory of her husband, as she firmly believes that his killer or killers remain at large.

“I feel like the state is pursuing them because they need to blame someone and they think they are doing justice. But what they have been doing is an injustice … This needs to stop, for me and my family to get closure.”

“I am speaking out now because I don’t want another innocent man to die in prison.”